This report shows how NHS England required NHS Kernow (the local clinical commissioning group) to produce a Sustainability and Transformation Plan (STP) but gave no advice on how to do it. NHS Kernow hired management consultants but allowed them to pursue their own agenda. NHS Kernow seem not to have considered ways of attracting funds from NHS England, and have missed opportunities to do so. Health care leaders have been distracted by high-level negotiations on ‘strategic integration’ from getting on with the day job: very recently the Care Quality Commission issued a Warning Notice requiring the Royal Cornwall Hospital Trust to make significant improvements at Treliske Hospital within a week(!), because longstanding concerns were persisting about the safety and quality of some services. And after health and social care staff at all levels recently ‘pitched in together’ and turned round a bad situation in the Emergency Department at Treliske, the important lesson from that is being missed.

* * *

There are two versions of this report. This is the FULL REPORT. It can be downloaded as a pdf here. There is also a SHORT REPORT, published simultaneously on this website. It too can be downloaded as a pdf, here.

Background

Basically, health and social care in Cornwall are run by five bodies. At national level, there is NHS England: it hands money to, and oversees, the local body NHS Kernow (officially Kernow Clinical Commissioning Group), which buys health services on behalf of local people. These services include acute hospital care, which is provided by Royal Cornwall Hospital Trust, and mental health care, which is provided by Cornwall Partnership Foundation Trust. The fifth body is Cornwall Council, which both pays for and provides social services across Cornwall.

Recently these bodies have been involved in a string of bungles. The cost, in terms of wasted time and effort and distraction from important tasks, not to mention actual money wasted, has been immense. This report highlights six of these bungles and their consequences, and identifies lessons that, if learned, could help avoid similar bungles in future. The body of the report is divided into three parts: Part I – Edicts from the Centre; Part II – The Bungles; and Part III – Lessons.

The period covered by the report runs from October 2014 to the present. The most significant events on the ‘timeline’ are shown in Box 1.

| Box 1: The timeline

October 2014: NHS England publishes Five Year Forward View.

July 2015: The Cornwall Devolution Deal is signed.

December 2015: Delivering the Forward View: NHS planning guidance: 2016/17 – 2020/21 published, introducing Sustainability and Transformation Plans.

October 2016: Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly: Sustainability and Transformation Plan: Draft Outline Business Case published.[1]

March 2017: Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View published: Sustainability and Transformation Plans get only one slight mention.

|

Part I – Edicts from the Centre

October 2014: NHS England publishes Five Year Forward View

In Five Year Forward View,[2] NHS England argued that ‘the health service needs to change’. The document made no significant references to plans, but set out a variety of new ‘care models’ that it would support (See Box 2). Accepting that ‘England is too diverse for a one-size-fits-all care model to apply everywhere’, it promised that local health communities would be supported by the NHS’s national leadership ‘to choose from amongst a small number of radical new care delivery options, and then given the resources and support to implement them where that makes sense’.

These new models of care were all described in non-technical language, rooted in day-to-day experience rather than a ‘vision’ or a ‘theme’. And Five Year Forward View gave concrete examples of ’emerging models’ already in use in various parts of the country.

|

Box 2: New Models of Care

The Multispecialty Community Provider (MCP) would permit groups of GPs to combine with nurses, other community health services, hospital specialists and perhaps mental health and social care to create integrated out-of-hospital care.

Primary and Acute Care Systems (PACS) where hospital care and primary care are integrated, so ‘combining for the first time general practice and hospital services’.

Urgent and emergency care services ‘redesigned to integrate between A&E departments, GP out-of-hours services, urgent care centres, NHS 111, and ambulance services’.

Help for smaller hospitals to remain viable, including forming partnerships with other hospitals further afield, and partnering with specialist hospitals to provide more local services.

Midwives would have new options to take charge of the maternity services they offer.

The NHS would provide more support for frail older people living in care homes.

List-based primary care would continue to be the foundation of NHS care, but a ‘new deal’ for GPs was needed. … ‘GP-led Clinical Commissioning Groups will have the option of more control over the wider NHS budget, enabling a shift in investment from acute to primary and community services.’

|

One of those warmly commended emerging models was very close to home:

In Cornwall, trained volunteers and health and social care professionals work side-by-side to support patients with long term conditions to meet their own health and life goals.[3]

This is evidently a reference to the Living Well scheme, which was set up and run by Age UK Cornwall.

Finally, finance was a major factor in the thinking behind Five Year Forward View. It was calculated that with growing demand, if there were no further efficiency savings and funding were kept flat in real terms, by 2020/21 patient needs would exceed resources by nearly £30 billion a year in England. It was hoped that new models of care would help to bring demand, efficiency and funding into balance.

NHS England would support these changes by providing ‘meaningful local flexibility’ in the way payment rules etc were applied. Local leadership and a variety of solutions would be supported, and innovation emphasised. But Five Year Forward View did not contain any requirement for clinical commissioning groups to produce plans.

December 2015: Delivering the Forward View: NHS planning guidance: 2016/17 – 2020/21 is published

It was 14 months after the publication of Five Year Forward View that Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs) came on the scene. They were announced in Delivering the Forward View: NHS planning guidance: 2016/17 – 2020/21, published in December 2015.[4] NHS organizations in different parts of England were asked to come together to develop plans for the future of health services in their area, including by working with local authorities and other partners. In Cornwall, the relevant area was the county, and conveniently only a single local authority, Cornwall Council, was involved.

The planning guidance required NHS bodies to produce two separate but connected plans:

A five-year Sustainability and Transformation Plan (STP), area-based, which would ‘drive’ the Five Year Forward View; and

A one-year Operational Plan, the first of which was to cover 2016/17, organisation-based but consistent with the emerging STP.

Every health and care system – clinical commissioning groups, [provider] trusts and local authorities – was being asked ‘to come together, to create its own ambitious local blueprint for accelerating its implementation of the Forward View’.

But how was the plan to be created? The planning guidance did not provide any kind of manual: there was no step-by-step set of instructions. All it had to say on the subject was this:

Producing an STP … involves five things: (1) local leaders coming together as a team; (2) developing a shared vision with the local community, which also involves local government as appropriate; (3) programming a coherent set of activities to make it happen; (4) execution against plan; and (5) learning and adapting.

Success also depends on having an open, engaging, and iterative process that harnesses the energies of clinicians, patients, carers, citizens, and local community partners including the independent and voluntary sectors, and local government through health and wellbeing boards.

… The STP must also cover better integration with local authority services, including, but not limited to, prevention and social care, reflecting local agreed health and wellbeing strategies.

The planning guidance did have something important to say about funding:

For the first time, the local NHS planning process will have significant central money attached. The STPs will become the single application and approval process for being accepted onto programmes with transformational funding for 2017/18 onwards.

There would also be additional dedicated funding streams for transformational change, covering initiatives such as the spread of new care models and to drive clinical priorities.

The earliest additional funding would go to the most ‘compelling and credible’ STPs. The selection criteria would include

The quality of plans, particularly the scale of ambition and track record of progress already made. The best plans will have a clear and powerful vision [and] create coherence across different elements.

The reach and quality of the local process, including community, voluntary sector and local authority engagement;

The strength and unity of local system leadership and partnerships, with clear governance structures to deliver them; and

How confident we are that a clear sequence of implementation actions will follow as intended … .

These are very subjective criteria, very much matters of judgment. To satisfy them, one has to know more precisely what the people in charge are looking for and what will please them. What, one might ask, will give a plan ‘funding appeal’? For some suggestions, see Box 6 below.

March 2017: Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View is published

This document, published on the NHS England website,[5] took stock of the progress that had been made since Five Year Forward View was published. It affirmed the NHS’s national leadership bodies’ shared vision of the Forward View and their approach to implementing it.[6] Interestingly, Next Steps … described itself as ‘this plan’, but primarily it amounted merely to a list of actions that NHS England was committing itself to take in the next two years. These included taking new models of care forward, especially those that had been developed in the fifty geographical areas that had taken part in the ‘Vanguard’ programme. See Box 3.

|

Box 3: The Vanguard programme

The Vanguard programme focused on:

Better integrating the various strands of community services such as GPs, community nursing, mental health and social care, moving specialist care out of hospitals into the community (‘Multispecialty Community Providers’ or ‘MCPs’);

Joining up GP, hospital, community and mental health services (‘Primary and Acute Care Systems’ or ‘PACSs’);

Linking local hospitals together to improve their clinical and financial viability, reducing variation in care and efficiency (‘Acute Care Collaborations’ or ‘ACCs’); and

Offering older people better, joined-up health, care and rehabilitation services.

|

Both MCP and PACS Vanguards had seen lower growth in emergency hospital admissions and emergency inpatient bed days than the rest of England.

As we see, Next Steps … reverted to the format of Five Year Forward View in that it highlighted practical developments, such as MCPs and PACSs, rather than plans which would require management consultants to flesh out.

So 15 months after the launch of Sustainability and Transformation Plans, with a fanfare and intimations of their importance for funding etc, they had been quietly dropped. What would take their place with regard to funding was not stated. But instead of the Plans there was to be a new way of working. Within an area, participating organisations, including all NHS bodies, would work in Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships. These would replace Sustainability and Transformation Plans as a mechanism for delivering the Forward View. Confusingly, the initials STP would now be used to refer to a Partnership.[7]

These partnerships were and still are seen as a way of bringing together GPs, hospitals, mental health services and social care. The emphasis is on integration. They would be a ‘forum’ in which health leaders linked together services and shared staff and expertise, so care would be safer and more effective. In contrast to the previous doctrine that competition was the guarantor of efficiency in the NHS, collaboration was now the order of the day.

A certain amount of local autonomy was also envisaged. The way the new STPartnerships worked would vary according to the needs of different parts of the country. The national health bodies did not want to be ‘overly prescriptive’ about organisational form. The new health and care systems were to be defined and assessed primarily by how they practically tackled their shared local health, quality and efficiency challenges.

Community participation and involvement

As the authors of Next Steps … saw it, the partnerships – the integrated health systems – needed to engage with communities and patients in new ways, to mobilize collective action on ‘health creation’ and service redesign. Making progress and addressing challenges could not be done without genuinely involving patients and communities.

Nationally, we will continue to work with our partners, including patient groups and the voluntary sector, to make further progress on our key priorities. Locally, we will work with patients and the public to identify innovative, effective and efficient ways of designing, delivering and joining up services.

Healthwatch England had set out five steps to ensure local people have their say: See Box 4.

| Box 4: Five steps to ensure local people have their say (Healthwatch England):

Set out the case for change so people understand the current situation and why things may need to be done differently.

Involve people from the start in coming up with potential solutions.

Understand who in your community will be affected by your proposals and find out what they think.

Give people enough time to consider your plans and provide feedback.

Explain how you used people’s feedback, the difference it made to the plans and how the impact of the changes will be monitored.

|

PART II – The Bungles

Bungle Number 1 The so-called ‘planning guidance’ on delivering the Five Year Forward View (which was actually not published until 14 months after Five Year Forward View appeared) required the production of Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs) but gave no guidance on how to produce them. It is clear that neither NHS England nor NHS Kernow had much idea how to do that. And 15 months after the ‘planning guidance’ appeared, the next policy document – Next Steps … – said nothing at all (apart from a brief passing mention) about STPs.

By any logic it would have made sense for the forward view and the planning guidance associated with it to be published together. The fact that they were not is a clear indication that central NHS policy-making machinery was not functioning well. The fact that a reorganization of regulatory/supervisory machinery was taking place at the time[8] will not have helped.

The late arrival of the instruction to prepare STPs had serious consequences for Cornwall. Not only, it appears, did NHS Kernow officers not know how to produce a Sustainability and Transformation Plan – it was demonstrably not something for which their training or previous experience had prepared them – but the so-called planning guidance provided almost zero actual guidance about how to go about creating these plans. NHS England officers side-stepped responsibility for this by placing the onus on local bodies to create ‘compelling’ plans and urging them to hire management consultants.

So for 15 months NHS Kernow officers were under pressure to devote time, money and scarce staff resources – already fully occupied – to producing an STP. They had to hire management consultants, at considerable expense – probably around £1.5 million. (Over England as a whole there were 44 STPs: the cost to the NHS must have been of the order of £60 million.) And then the plans were quietly put to one side. By any reckoning, this was a major and costly bungle by NHS England.

Bungle Number 2 NHS Kernow spent money on management consultants but did not turn a critical eye on their work. The consultants did what consultants do: they wrote their own brief and produced a ‘target operating model’ and a ‘business case’, not a plan. Not producing what NHS England asked for was hardly guaranteed to win funds.

The ‘Target Operating Model’ was presented in Outline Business Case[9] as a kind of culminating achievement. Its stated purpose was ‘to provide a high-level understanding of how we will work together as a single, co-ordinated system in order to deliver services on a whole population basis …’. The diagram and language are not those of Five Year Forward View or even the ‘planning guidance’: they come straight from the world of business management consultancy, as a web search for ‘target operating model’ instantly reveals. Although their involvement was nowhere acknowledged, it is apparent that Outline Business Case was at least in part ghost-written by management consultants. The firm Price Waterhouse Coopers (PwC) was involved at this stage.[10]

In February 2017 NHS Kernow’s Interim Chief Officer informed its Governing Body:

We have engaged GE Healthcare Finnamore as a Strategic Partner for Shaping our Future. [This title had been adopted as the ‘brand name’ for the STP programme.] The first task is to establish the robust evidence, modelling and activity analysis required for the proposals for the pre consultation business case and how developed this currently was.(sic) [11] [12]

Not only does this statement illustrate how easy it is to slip into using management-consultant-speak: observe how smoothly Finnamore has been elevated to the position of ‘strategic partner’. This would accord them a status well above that of a hired contractor.

The first fruits of this contract, which is said to have cost up to £1.2 million,[13] emerged in March 2017, in the form of a report, entitled Final Report – Part 1 Support, which was subsequently obtained through a Freedom of Information enquiry and published by Cornwall Reports.[14] Much of the report is written in management-consultant-speak – ‘Testing the TOM for Architectural Coherence’, ‘Granularity of OBC content and supporting documentation is not at the level of maturity required to achieve a PCBC in the timescales proposed’ – but the consultants reported, clearly enough, that they had ‘assessed readiness for the development of a pre consultation business case (PCBC) to take forward the STP priorities in Cornwall’.

In a detailed analysis of the organization’s readiness, the consultants found that ‘two thirds of the elements required for a PCBC have not yet commenced or need additional work. Workstream leads recognise that there are considerable gaps in the data and information needed for a PCBC’. Much additional work would be needed over the coming months to deliver a robust and comprehensive case.

There is no sign of NHS Kernow having carried out a risk analysis before hiring management consultants and putting unquestioning trust in them. Although in clinical commissioning groups (and NHS trusts and local authorities) it is normal for the risk attached to a spending proposal to be assessed (conventionally using a coding of red, amber and green to denote high, medium and low levels), that evidently was not done in this case.

But risks are certainly entailed. The risks of hiring management consultants to work on health and social care are summarized in Box 5.

| Box 5: The risks of hiring management consultants to work on health and social care

They will have their own agenda, which will not be the same as yours. They will want a distinctive product to help them market their services to prospective future clients, which will not be one of your concerns.

They will speak their own language, management-consultant-speak. If you do not, this will make it difficult for you to question their methods and assumptions.

They will not necessarily have an intuitive grasp of concepts like ‘funding appeal’. And they may not be schooled in political sensitivity, an invaluable attribute in the world of health and social care and central-local relations.

You will become their ‘captive’, dependent on their advice. So (a) you will get to think in their terms, use their language, and see issues in the way that they do; and (b) there will be difficulties and penalties attached to going against their advice, and consequently your freedom of action will be diminished.

They will cost you.

On the other hand, if you allow independent consultants to examine how your organization operates, they may be able to identify – from their experience elsewhere – obstacles to effective working, and ways of getting round them, that you are too involved or too inexperienced to see. The benefits of this ‘carrier pigeon’ function of independent consultants should not be overlooked.

|

An investigation by the King’s Fund found that the use of management consultants was routine. ‘Some leaders felt that STPs had created an industry for management consultants – and questions were raised about why money is being invested in advice from private companies instead of in frontline services.’ In one area, STP leaders even felt under pressure from NHS England’s regional team to increase the amount of money they were spending on management consultancy support. And in one STP area that had not directly commissioned external support to develop its plan, NHS England’s regional team had commissioned a management consulting firm to carry out analytical work on behalf of its STP areas.[15]

In the NHS, public spending on management consultants more than doubled from £313 million in 2010 to £640 million in 2014. A recent study carried out in English NHS hospital trusts by Ian Kirkpatrick et al found that instead of improving efficiency, the employment of management consultants was more likely to result in inefficiency. They concluded that while efficiency gains are possible through using management consultancy, this is the exception rather than the norm. ‘Overall, the NHS is not obtaining value for money from management consultants and so, in future, managers and policy makers should be more careful about when and how they commission these services.’ More thought could also be given to alternative sources of advice and support, from within the NHS, or simply using the money saved on consulting fees to recruit more clinical staff.[16] However, as noted at the foot of Box 5, their contribution may come in other forms besides ‘advice and support’.

Bungle Number 3 NHS Kernow failed to talk to NHS England in their own language. There is a golden rule for winning money from a funding body: ‘In your application speak to the fund-giver in their own language.’ You really do not want the fund-giver to have to decipher or puzzle over your application.

There is one very obvious illustration of this failure. NHS Kernow was asked to produce a Sustainability and Transformation Plan: what they submitted – no doubt as a consequence of their reliance on business management consultants – was a business case. A business case sets out a justification for a course of action, but it is not of itself a plan.

Again, in March 2017 GE Healthcare Finnamore were anticipating that the next step in the STP process would be to develop ‘a pre consultation business case (PCBC) to take forward the STP priorities in Cornwall’, and this has gone unchallenged by NHS Kernow. Once again, a case, even a refined one, does not amount to a plan.

Similarly, NHS Kernow failed to register that when Five Year Forward View highlighted new models of care that it would promote or permit, this was a clue that their case/plan should do the same. Instead their Outline Business Case merely said ‘we will have created and embedded a new model of care’: it did not relate this aim to any of the models that NHS England had said it intended to promote or permit, such as MCTs and PACSs.

As already noted, for proposals to gain funding, they must have ‘funding appeal’, and to this end they must be expressed in language with which those who control funds are comfortable and feel at home. For some suggestions, see Box 6.

| Box 6: ‘Funding appeal’

In effect, what Delivering the Forward View provided was a kind of recipe for ‘funding appeal’: how to construct and present an STP in such a way as to attract the maximum of funding from NHS England. Not all of the criteria are crystal clear: how does one assess ‘the reach and quality of the local process’, for example, or gauge what will be found ‘compelling and credible’ by different national NHS bodies?

But probably the prime criterion by which applications would initially be screened would be that the winners recognise that they have to think about what is meant by ‘reach and quality’: it won’t even occur to the laggards that they need to do this.

As probably every successful grant-aided voluntary organization knows, to succeed with a grant application it is necessary to master the brief: not only to read the rules but also to read between the lines and understand and interpret the message at every level. Then the submitted application should use the same or similar language, meet implicit as well as stated requirements, and give relevant practical examples. It is clearly counter-productive if the grant giver has to spend time deciphering or puzzling over your bid for funds.

|

Bungle Number 4 NHS Kernow damaged its own credibility by abandoning the Living Well project and putting nothing in its place. It was one of very few local bodies to get a mention in Five Year Forward View: As noted above, ‘In Cornwall, trained volunteers and health and social care professionals work side-by-side to support patients with long term conditions to meet their own health and life goals.’ This was the Living Well programme, run by Age UK Cornwall.

The Living Well programme ended in September 2016, after Age UK Cornwall had asked for a grant of £9.5 million (to be spread over 5 years) to enable it to continue. The request was not supported by a business case, and with NHS Kernow’s financial plan for 2016/17 showing a forecast end-of-year deficit of £38.8 million, it was declined.

What is significant is that no steps were taken to ensure that the learning from the project was not lost, or to find ways of continuing the work under different auspices or on a lesser scale. So NHS Kernow gave up this source of its credibility with NHS England. Shooting oneself in the foot in this way is hardly likely to reflect well on an organization’s leadership qualities, which would be a factor in assessing any request for funding.[17]

It is noteworthy that in the summer of 2017 a team from Cornwall Council and NHS Kernow, charged with commissioning a new contract for Home Care Services and Supportive Lifestyles, reported on work they had been doing on a new ‘delivery model’ for services for adults over the age of 18 years who have eligible health and/or social care needs and include people with physical disabilities, learning disabilities, sensory loss and age related needs.[18] The team had organized engagement sessions and workshops with care and support providers, people receiving services or who might require services in the future, and staff from health and social care partners. These sessions/workshops had looked at ‘the current market position, exciting new marketing opportunities for present and future businesses and highlight the gaps in the market’. Strikingly, the report makes no mention whatever of volunteers and how they might be deployed alongside paid staff.

Five Year Forward View had highlighted the importance of involving volunteers within the NHS and wider communities. ‘Volunteers are crucial in both health and social care. Three million volunteers already make a critical contribution to the provision of health and social care in England.’[19] This aspiration had evidently not registered in Cornwall. The Living Well project, and the volunteers mobilized as part of it, might never have existed.

Bungle Number 5 Bundling together of ‘communications’ and ‘engagement’ is rife all over the NHS, in management positions, teams, strategies etc.[20] Unfortunately they are fundamentally very different activities, calling for very different skills, and when they are confused, as has happened in Cornwall, so-called engagement can engender a great deal of suspicion.[21]

Communications experts, who in many cases have had a training in journalism, are trained to make use of the media: to ‘put the message out’ and put a positive gloss on it, to persuade, and even to ‘spin’. Insofar as they listen, it is in order to see how their message has been received and to improve their delivery of it.

In contrast, successful engagement requires some of the attributes of the social researcher. It calls for the asking of unbiased, non-loaded questions. It involves dialogue, two-way communication: it requires skills in listening rather than selling, in appreciating what others are saying, in responding appropriately, in gaining other people’s confidence and being open and ‘straight’ with them and able to negotiate compromises. It is a completely different skillset from that of the ace communicator.

So when we have communications specialists involving themselves in engagement, we often find persuasion slipping in. An example of this is provided by the ‘co-production workshops’ that are coming to form an important part of the Shaping our Future programme:

A place-based model of care is being developed … in six local areas in Cornwall … Up to four waves of co-production workshops are being held in each locality to design the new model …[22]

These workshops are a mixture of presentation and discussion. It is the presentations and the information packs handed out with them that are problematic, because here is where persuasion slips in. For example, at the first set of workshops the information pack included a section on ‘The case for change’, which contained five snippets of quantitative data on hospital services:

Around 60 people each day are staying in acute hospital beds in Cornwall and they don’t need to be there.

35% of community hospital bed days are being used by people who are fit to leave.

Older people can lose 5% of their muscle strength per day of treatment in a hospital bed.

83% of admissions to community hospitals are from acute services compared to 42% nationally.

62% of hospital bed days are occupied by people over 65 years old.[23]

Taken in conjunction with the reference in the draft Outline Business Case to ‘outdated, expensive bed-based’ care,[24] the first three snippets can be read as an attempt to persuade workshop participants that it is futile and wrong-headed to resist the closure of hospital beds, especially those in community hospitals. They are a particular selection of facts that support a ‘case for change’: they impart a certain ‘slant’ to the discussion. (As for the fourth and fifth snippets of data, including them seems to have no purpose other than making the case for closure appear to be supported by more statistics.)

Of course, people who no longer need to be in an acute or community hospital are not necessarily fit to go home, although – in the absence of information about other options, such as care homes or sheltered housing – this seems to be the conclusion we are intended to draw. Interestingly, we are not told what percentage of their muscle strength older people can lose per day if they are sent home to convalesce, without on-site re-ablement services.

As we see, the information presented in the information pack, seemingly calculated to justify the closing of hospital beds, is scanty and arbitrary, and presented in the form of snapshots. These represent situations at particular points in time or over particular periods. We are not told at what particular points in time, or over what particular periods, the data were collected. This is not good professional practice, and reflects poorly on the South West Academic Health Science Network, which provided the data.[25]

The infiltration of presentation techniques into what are ostensibly ‘engagement’ events is continuing at the present time. A current example is the technique of ‘spurious endorsement’. A briefing note for the Wave 3 ‘co-production workshops’ refers to a modelling tool as having been ‘endorsed by … the London School of Economics’ when in fact it had been endorsed by one individual professor.[26][27] Likewise, a draft specification for a GP-led Urgent Treatment Centre service referred to it having been ‘shared with’ the Citizen Advisory Panel: it was not approved by, or even scrutinized by, the Panel, but merely shown to them.[28] What we have here is what one might call ‘endorsement by name-dropping’: a presentation/ communication technique, but not one of genuine engagement.

Bungle Number 6 Issues around ‘accountable care organizations/systems’ and ‘integrated strategic commissioning’ have been preoccupying local leaders in the health and care system. Huge amounts of time and energy have been devoted to wrangling about organizational structure. (Or, as those in charge like to put it, ‘governance’.) At the time of writing, the Transformation Board, which itself started life as the Joint Strategic Executive Committee, is in the process of mutating into a ‘System Assurance Group’.[29] And a debate is taking place about the structure required for a strategic integrated commissioning function. In all this, the local leaders have been taking their eyes off what has been happening to patients and clients, as a string of critical reports from the Care Quality Commission attests.[30]

But while this high-level debate has been going on, something remarkable has been happening very recently at the ‘coalface’. In Box 7 is an extract from a report about recent events in the Emergency Department at the Royal Cornwall Hospital, Treliske. It describes a major turn-round in performance, basically achieved by everyone ‘pitching in together’, as one might say.[31]

| Box 7. A remarkable turn-around at Treliske

‘In March 2018, Cornwall A&E Delivery Board established a Gold Command in response to unprecedented levels of demand on urgent and emergency care services, leading to the Royal Cornwall Hospitals Trust being in a constant state of escalation for many weeks. Patients were experiencing long waits to be seen in the Emergency Department (ED) in Truro, some patients were having to be cared for in the corridor and high number of beds were closed due to flu or norovirus. Some planned surgery needed to be cancelled due to the pressures within the hospital. High numbers of patients in acute and community hospitals were being held up in their transfer home or on to another care setting. Also, ambulances had regularly been unable to transfer their patients into ED due to overcrowding with a consequent adverse effect on ambulance responsiveness.

‘The Gold Command approach brought together Chief Executives, senior clinicians and operational managers from across health and social care twice daily every day to work intensively together at every level, deploying additional resources, in order to return to a position where people had access to safe health and social care.

‘The achievements of this intensive system approach have been extraordinary. There have been significant improvements for example in ambulance lost time, delayed transfers of care and the provision of timely care within the Emergency Department. GPs have been working alongside their hospital colleagues, community services and social care have provided additional resources to support patients’ discharge and improvements have been made in transport booking to support patients to be in the most appropriate setting for their needs. Many staff made themselves available for extra shifts. In the lead up to Easter, for the first time in recent memory, Cornwall was on the lowest level of operational alert: Operational Pressure Escalation Level 1 (formerly ‘green’). Emergency Department performance has been above the national standard of 95% and local hospitals greatly reduced the number of long stay, medically fit patients. Indeed, performance on the 4 hour Emergency Access Standard was the best for any Trust in the South of England.’

|

However, comments by people concerned with governance reveals that they see things differently:

Developing a fully functioning Integrated Care System is a complex process and would need to be a multi-stage process, requiring a developmental and incremental approach. With organisations working together in 2018/19, subject to approval, to test the concept, review and refine the model and progressing through a series of phases. Mobilisation, Design, Refine and finally Operational subject to the appropriate approval processes.[32]

So the Treliske experience risks being taken to justify a complex, multi-stage process. It is hard to see that leading to anything other than a complex system to oversee it. We are witnessing a failure to learn from this recent experience and grasp the notion of ‘pitching in together’.

The right lesson is not being drawn from this heartwarming story. Given the resources, the freedom and the responsibility, there are people at ‘ground level’ – those who actually deliver the service – who are very capable of doing a good job, of responding to emergencies in an agile, enterprising and enthusiastic way, and the last thing they need is a complex system overseeing them. They have taught themselves to work in an ‘organic’ as opposed to ‘mechanistic’ or ‘hierarchical’ way.[33] Arguably, too, this kind of experience – bottom-up, not top-down – will do more to attract funding from NHS England than any amount of tinkering with governance.

But we have to ask: Is the Transformation Board and are the staff working under it actually equipped to learn from the experience at Treliske? Are they able to analyse it, to understand the part played in its success by different factors, such as communication, hierarchy (or the lack of it), and personalities? This is a situation where independent research could make an invaluable contribution.

Part III – Lessons

This study suggests a number of lessons, one for each of the bungles identified.

1. A lesson for NHS England: When local health and social care systems are being asked to do something that they haven’t done before, they should be given properly-tested guidance at the time, not left to divert already-stressed staff resources into having to guess what is required of them.

2. Before agreeing to hire business management consultants, local bodies should be very clear what they need and should conduct a risk analysis. They should not be regarded as ‘partners’.

3. Local bodies must appreciate that it is crucial for them to be able to talk to NHS England and other central agencies in their own language. There may be scope for consultants to offer masterclasses in reading the publications of NHS England and NHS Improvement.

4. Before deciding to create or abandon a project, local bodies should assess not only the immediate financial implications, such as their attractiveness to funding bodies, but the wider impact too, such as their scope for involving volunteers.

5. Central and local bodies should appreciate that ‘communications’ and ‘engagement’ are very different activities, and require different skillsets. They should emphatically not entrust communications specialists with organizing engagement events. And they should appreciate that for engagement to be effective it needs to take place throughout a planning process, as Healthwatch England has pointed out, not tacked on in a public consultation phase when many possibilities will already have been pre-empted and foreclosed.[34] (See Box 4.)

6. Local leaders should avoid being distracted by high-level ‘strategic’ organizational issues from paying attention to what is happening on the ground. Designing an organizational structure should start from ground level, from seeing ‘what works’: working from the bottom up, not from the top down. And it should be appreciated that this is difficult, not to be left to people who find themselves in senior positions but who have never had the benefit of studying how organizational structures can be created. NHS England would do well to sponsor research and instruction in this field.

Notes and references. All websites accessed on April 8th, 2018.

[1] I apologise to the inhabitants of the Isles of Scilly, but it is in the interest of brevity that elsewhere in this report I refer to the Sustainability and Transformation Plan as Cornwall’s STP. Officially it is indeed the STP for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly.

[2] NHS England, Five Year Forward View, October 2014

https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf

No author given, but the Foreword says: ‘It represents the shared view of the NHS’ national leadership, and reflects an emerging consensus amongst patient groups, clinicians, local communities and frontline NHS leaders.’ And the back cover bears the imprints (logos) of Care Quality Commission, NHS England, Health Education England, Monitor, Public Health England, and Trust Development Authority.

[3] As [2], p.17

[4] NHS England et al, Delivering the Forward View: NHS planning guidance: 2016/17 – 2020/21, December 2015

https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/planning-guid-16-17-20-21.pdf

[5] (Authorship not stated) Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View, March 2017

https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEXT-STEPS-ON-THE-NHS-FIVE-YEAR-FORWARD-VIEW.pdf

[6] These bodies were NHS England, NHS Improvement (formed in April 2016 by combining Monitor, NHS Trust Development Authority and other regulatory and supervisory bodies), the Care Quality Commission, Public Health England, Health Education England, NHS Digital and NICE, and various patient, professional and representative bodies.

[7] To avoid confusion, in this report I shall continue to use STP to refer to the plans and STPartnership to refer to the organization.

[8] The organization NHS Improvement was in the process of being formed by combining Monitor, NHS Trust Development Authority and other bodies.

[9] Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly: Sustainability and Transformation Plan: Draft Outline Business Case. October 2016

https://www.cornwall.gov.uk/media/22984634/cornwall-ios-stp-draft-outline-business-case.pdf

[10] Cornwall Reports, 15 February 2017 : Cornwall’s STP brings in the Chicago gang to advise on £264 million health and social care cuts

https://cornwallreports.co.uk/cornwalls-stp-brings-in-the-chicago-gang-to-advise-on-264-million-health-and-social-care-cuts/

[11] Minutes of KCCG Governing Body meeting 7 February 2017

https://doclibrary-rcht.cornwall.nhs.uk/DocumentsLibrary/KernowCCG/OurOrganisation/GoverningBodyMeetings/1617/201703/GB201617143GBMinutesAndActionGrid.pdf

[12] GE Healthcare Finnamore started life as the British consultancy Finnamore: it was taken over by the American global conglomerate General Electric in 2014.

[13] As [10].

[14] GE Healthcare Finnamore, Final Report – Part 1 Support, 23 March 2017

https://cornwallreports.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/GE-FIRST-REPORT-ilovepdf-compressed-2.pdf

[15] Hugh Alderwick, Phoebe Dunn, Helen McKenna, Nicola Walsh, Chris Ham, Sustainability and transformation plans in the NHS: How are they being developed in practice? November 2016

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/stps-in-the-nhs

[16] Ian Kirkpatrick et al, Using management consultancy brings inefficiency to the NHS, March 2018

http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/using-management-consultancy-brings-inefficiency-to-the-nhs/

I Kirkpatrick et al, The impact of management consultants on public service efficiency, Policy & Politics, April 2018http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/tpp/pap/pre-prints/content-pppolicypold1700072r2;jsessionid=25vwj4q8vscjk.x-ic-live-01

[17] On this saga see P. Levin & K. Maguire, Where now for ‘Living Well’ in Cornwall?, 13 August 2016

http://westcornwallhealthwatch.com/where-now-living-well-cornwall

[18] Cornwall Council, NHS Kernow, Home Care and Supportive Lifestyles Services, September 2017

https://www.cornwall.gov.uk/media/29035134/stakeholder-engagement-and-coproduction-report.pdf

[19] As [2], p.13, and see NHS Employers, Recruiting and retaining volunteers, 19 April 2016

http://www.nhsemployers.org/case-studies-and-resources/2016/04/recruiting-and-retaining-volunteers

[20] See NHS Improvement, Toolkit for communications and engagement teams in service changes programmes, undated, but June 2016

https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/163/10473-NHSI-Toolkit-INTERACTIVE-04.pdf

[21] Peter Levin, Communications and engagement in health and social care: A cautionary tale from Cornwall, 12 July 2017

https://spr4cornwall.net/communications-and-engagement-in-health-and-social-care-a-cautionary-tale-from-cornwall/

[22] Transformation Board meeting, 19 December 2017: Consolidated Performance Management Report, November 2017. p.15.

http://doclibrary-shapingourfuture.cornwall.nhs.uk/DocumentsLibrary/ShapingOurFuture/TransformationBoardMeetings/Minutes/1718/201712/ProgrammeDirectorHighlightReport.pdf

[23] https://spr4cornwall.net/170707-info-pack-west-cornwall-final/

[24] p.43. The OBC does put the case for hospital bed closures in the context of the need for more housing options, which the handout failed to do.

[25] https://www.swahsn.com

[26] Briefing on Shaping Our Future urgent care work stream progress (undated, but February 2018).

https://spr4cornwall.net/wp-content/uploads/Briefing-on-Shaping-our-Future-Urgent-Care-work-stream-progress-Feb-2018.pdf

[27] NHS England, Urgent & Emergency Care: Consolidated Channel Shift Model: User Guide, Feb 2017

https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/uec-channel-shift-model-user-guide.pdf

[28] DRAFT Service Specification, GP-led Urgent Treatment (UTC) Service (undated, but February 2018).

https://spr4cornwall.net/wp-content/uploads/DRAFT-Specification-GP-led-UTC-Service.pdf

[29] Transformation Board: Minutes of meeting 19 December 2017, Item 4c.

http://doclibrary-shapingourfuture.cornwall.nhs.uk/DocumentsLibrary/ShapingOurFuture/TransformationBoardMeetings/Minutes/1819/201804/TransformationBoardMinutesDecember2017.pdf

[30] On 6 April 2018, CQC issued a Warning Notice requiring the Royal Cornwall Hospital Trust to make significant improvements within a week. Professor Ted Baker, Chief Inspector of Hospitals, said: ‘It is disappointing to report that our longstanding concerns persist about the safety and quality of some services at Treliske Hospital.’

https://www.cqc.org.uk/news/releases/cqc-inspectors-call-further-improvements-patient-services-royal-cornwall-hospital

[31] Transformation Board: Agenda paper for meeting 6 April 2018, Item 6.

http://doclibrary-shapingourfuture.cornwall.nhs.uk/DocumentsLibrary/ShapingOurFuture/TransformationBoardMeetings/Minutes/1819/201804/DevelopmentOfAnIntegratedCareSystem.pdf

[32] As [31].

[33] On mechanistic and organic structures, see the classic work by Tom Burns and G.M. Stalker, The Management of Innovation (Oxford UP, Revised edition 1994)

[34] Peter Levin, Cornwall’s STP: Why we need to see what’s going on, 12 September 2017

https://spr4cornwall.net/cornwalls-stp-why-we-need-to-see-whats-going-on/

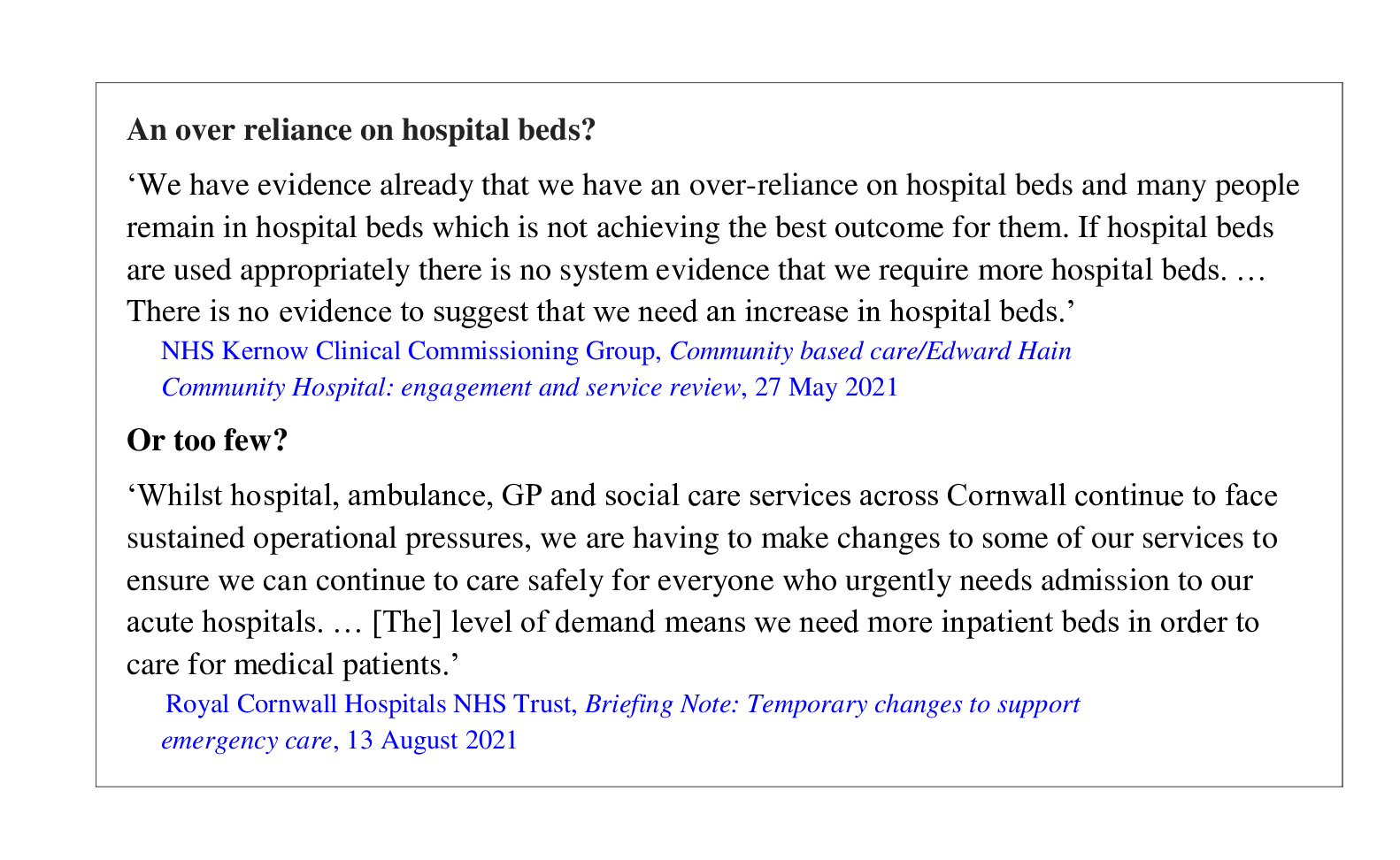

They can’t both be right. But might they both be wrong? This paper examines the two claims and finds both wanting.

They can’t both be right. But might they both be wrong? This paper examines the two claims and finds both wanting.